1. Introduction – Boo.com

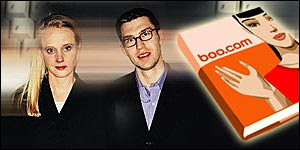

In the late 1990s, Boo.com emerged as one of the most hyped and lavishly funded e-commerce ventures of the dot-com era. Launched in 1999 by Swedish entrepreneurs Ernst Malmsten, Kajsa Leander, and Patrik Hedelin, Boo.com aimed to revolutionize how people shopped for fashion online. With a vision of selling branded streetwear and luxury items to a global youth audience, the company sought to combine cutting-edge technology, bold design, and an immersive user interface.

At its peak, Boo.com raised over $135 million in venture capital, set up offices in multiple countries, and employed more than 400 people. The website was packed with interactive features, 3D-animated avatars, a virtual shopping assistant named “Ms. Boo,” and live customer service – ahead of its time but also burdened by internet limitations of the era. Boo.com launched in 1999 but collapsed just six months later in May 2000. The site was inaccessible to most users due to its heavy reliance on Flash and JavaScript, both uncommon in mainstream internet browsing at the time. Slow load times, poor usability, and overengineering plagued its operations.

The company’s rapid fall from grace became emblematic of dot-com hubris. Boo.com’s failure highlighted a mismatch between ambition and execution, and a critical underestimation of consumer internet capabilities. Its brief but spectacular story remains one of the most cited cautionary tales in tech startup history.

2. Company Background – Boo.com

- Founded: 1998

- Launched: November 1999

- Founders: Ernst Malmsten, Kajsa Leander, Patrik Hedelin

- Headquarters: London, UK

- Business Model: Online fashion retailing

- Funding Raised: $135 million from firms like J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, and LMVH

- Number of Employees: Over 400 at peak

- Initial Market: UK, with plans for international reach including the US, Germany, and France

Boo.com was established as an e-commerce platform targeting fashion-forward consumers who wanted premium branded apparel online. It planned to build a global customer base from day one—a massive challenge given that most internet users in 1999 were still on dial-up connections.

What made Boo.com unique at the time was its decision to prioritize style and branding above all else. It launched with a highly stylized website with unique fonts, animated navigation, and interactive customer support avatars. The founders envisioned Boo.com as a new kind of fashion experience, merging lifestyle branding with cutting-edge tech.

However, while its vision was aspirational, its infrastructure, marketing, and technical execution failed to support such a grand idea. The company attempted to scale globally without first validating its core model in a single market.

3. Timeline of Key Events – Boo.com

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1998 | Boo.com is founded by Malmsten, Leander, and Hedelin |

| Early 1999 | Raises over $80 million in funding during design and beta stages |

| Nov 1999 | Official website launch with multilingual and multi-currency support |

| Dec 1999 | Criticism arises over slow-loading pages and poor usability |

| Jan 2000 | Expands staff to over 400 and launches marketing in several countries |

| Mar 2000 | Starts running out of cash; seeks $20M emergency funding |

| May 2000 | Fails to secure funding; files for bankruptcy and shuts down |

| June 2000 | Boo.com’s brand and assets sold for $375,000 |

4. Financial Overview – Boo.com

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Total Funding Raised | $135 million |

| Monthly Burn Rate | $8 million |

| Revenue Before Collapse | Less than $600,000 |

| Users at Peak | Estimated 300,000+ |

| Average Order Value | $60–$100 |

| Cost Per Order (Est.) | $125+ |

| Time in Operation | ~6 months |

Boo.com’s financials were catastrophic. The company burned through cash at an alarming rate, spending lavishly on international office spaces, custom-built backend systems, consultants, and branding exercises. The cost of customer acquisition and operations far exceeded the revenue, and the business never got close to breakeven.

The company’s backend was also custom-built and complex, leading to inefficiencies in inventory management and order processing. Combined with its oversized marketing spend and expensive staff hires (including a team of 30 PR specialists), the financials made the business unsustainable without continued investor support.

5. SWOT Analysis – Boo.com

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| Innovative branding and UI/UX design | Poor website performance on dial-up connections | Rising interest in online fashion shopping |

| Strong early investor backing | Overspending on tech and offices | Global scalability of e-commerce in coming decades |

| First-mover advantage in online fashion | Lack of focus on one market before global rollout | Use of mobile internet and apps (though premature) |

| Global multi-language site at launch | Burned too much capital too quickly | Brand had cultural cachet that could be leveraged later |

| Threats |

|---|

| Lack of broadband adoption among consumers |

| Heavy competition from simpler, faster e-commerce sites |

| Rising skepticism toward unprofitable dot-coms during 2000 downturn |

| Technology dependencies made updates and patches slow |

6. Porter’s Five Forces Analysis – Boo.com

Threat of New Entrants

Boo.com entered the market during a time of low barriers to entry in the e-commerce industry. With the dot-com bubble attracting massive investor attention, capital was easy to raise. This created a market saturated with startups trying to replicate success in different verticals, including fashion. Boo.com faced significant risk from smaller, more agile startups that could enter the market without the high infrastructure and R&D costs Boo.com bore. Moreover, the brand did not secure exclusive partnerships or technological IP that would make replication difficult. This intensified the competitive pressure.

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Boo.com relied on partnerships with multiple fashion brands and distributors. The suppliers, particularly high-end fashion brands, held considerable power. They were hesitant to allow a new e-commerce platform to control how their luxury products were displayed and sold online. Boo.com failed to build exclusive supplier relationships that could secure competitive pricing or guaranteed inventory access. Furthermore, many luxury brands were wary of online retail’s implications for brand prestige, weakening Boo.com’s position further.

Bargaining Power of Buyers

Online shoppers, particularly in the fashion industry, are highly price-sensitive and demand-rich content to make informed decisions. While Boo.com provided an advanced user interface with 3D models and virtual assistants, its prices were premium, and its product offerings were not unique. Customers could easily switch to other platforms with simpler UX or better prices. Additionally, the complexity of its website turned away many non-tech-savvy users, which further empowered consumers to look elsewhere.

Threat of Substitutes

Traditional retail stores remained the dominant force in fashion retail during the late 1990s. Customers still preferred in-store experiences, particularly when buying luxury items. Brick-and-mortar stores offered immediate gratification, tactile feedback, and personalized service. Additionally, other simpler e-commerce platforms and catalogs posed a serious threat by providing straightforward interfaces, better delivery assurances, and easier navigation.

Industry Rivalry

Rivalry in the online fashion retail segment was intensifying. While Boo.com was one of the first to attempt luxury fashion online, it did not anticipate the rise of leaner competitors. Sites like Net-a-Porter, which launched in 2000, focused on simpler UX and more curated shopping experiences. Boo.com also faced rivalry from generalist e-commerce platforms like Amazon and niche players who prioritized function over tech flash. The intense competition, coupled with Boo.com’s inability to generate revenue, led to unsustainable operations.

7. PESTEL Analysis – Boo.com

| Factor | Description | Impact on Boo.com |

|---|---|---|

| Political | No clear regulations for online international retail and digital taxation policies varied by country. | Made international expansion challenging and created uncertainty in cross-border operations. |

| Economic | Operated during the height of the dot-com bubble, with capital easy to raise but profit sustainability ignored. | Encouraged overspending on unproven technology and rapid scaling without validation of market demand. |

| Social | Consumers were still transitioning to online shopping. Internet access was not universal, especially in Europe. | Boo.com overestimated tech-savviness and digital readiness of mainstream consumers, leading to poor adoption. |

| Technological | Boo.com pioneered in interface design using JavaScript, Flash, and 3D avatars. | Technology was too advanced for dial-up speeds of 1999, making the site slow and inaccessible to most users. |

| Environmental | No strong push for environmental sustainability in retail or e-commerce at the time. | Environmental concerns had minimal influence on business strategy or user behavior in Boo.com’s operational window. |

| Legal | Laws surrounding online transactions, data privacy, and returns were still evolving across the EU and US. | Created logistical headaches and confusion around tax, customs, and consumer rights. |

8. Strategic Failures – Boo.com

Boo.com’s most critical strategic failure was its overinvestment in unproven technology without confirming product-market fit. The platform’s interface was cutting-edge but incompatible with user internet speeds at the time. JavaScript-heavy design, Flash animations, and 3D avatars resulted in a painfully slow experience for most users, especially on dial-up connections. This alienated customers who simply wanted to browse and buy clothes quickly. The ambition to redefine online shopping was not matched by technological feasibility or user readiness.

Secondly, the company burned through its $135 million funding within 18 months. A large portion went into website development, global marketing campaigns, and opening multiple international offices before revenue models were validated. The operational costs of running offices in New York, London, Paris, and Munich were unsustainable. It also overhired – more than 400 employees worked at Boo.com at its peak, adding to the fixed cost burden without driving proportional revenue growth.

Moreover, Boo.com tried to be everything at once – a high-tech interface innovator, an international retailer, a luxury fashion marketplace, and a logistics operator. It stretched itself thin with no single focus, and the absence of a defined niche or core market left it vulnerable. Instead of focusing on a single region or fashion segment, Boo.com attempted global dominance too early.

Leadership also misread market dynamics. In targeting luxury consumers, it failed to recognize that such buyers demanded tactile engagement and trusted brands. The idea of buying expensive apparel online without trying it on was foreign to most high-end customers in 1999. Boo.com didn’t provide enough support to bridge this psychological gap.

9. Collapse and Liquidation – Boo.com

By May 2000, just 18 months after its launch, Boo.com declared bankruptcy. The site had reportedly lost $135 million of investor capital. Without additional funding and with no revenue to sustain operations, the firm collapsed under its own weight. The final blow came when investors backed out of a planned funding round amid growing skepticism about dot-com profitability. Co-founders Ernst Malmsten and Kajsa Leander were ousted from the board prior to the final wind-down.

When Boo.com shut down, it left unpaid bills with suppliers, landlords, and service vendors across its offices. Its intellectual property and website assets were acquired by Fashionmall.com for a small sum – approximately $375,000. This was a stark contrast to its previous valuation, which had exceeded $135 million. The company’s brand was tarnished, and it became synonymous with dot-com failure.

Boo.com’s failure also triggered broader concerns in the VC ecosystem. Many investors, including Goldman Sachs and J.P. Morgan, suffered losses, leading to a more conservative investment strategy across the dot-com space. The media labeled it the epitome of startup excess – a cautionary tale for entrepreneurs prioritizing ambition over fundamentals.

10. Strategic Legacy and Lessons Learned – Boo.com

Despite its dramatic failure, Boo.com had a lasting impact on e-commerce and startup culture. It demonstrated the importance of aligning technology with user capabilities. While the platform was visionary in interface design, it failed to account for basic infrastructure realities – such as internet speed and device compatibility. In this sense, Boo.com was a pioneer that came too early.

Modern fashion e-commerce platforms have adopted many Boo.com innovations – from rich product views to virtual styling assistants – but have implemented them gradually, with user experience and load speed in mind. The lesson here is that being technologically advanced isn’t enough; timing, accessibility, and usability are equally critical.

Additionally, Boo.com highlighted the dangers of uncontrolled expansion. Its rush to establish a global presence drained resources and diverted focus from building a stable core market. Future e-commerce giants like Zalando and ASOS succeeded by focusing regionally before scaling internationally.

Investor sentiment also shifted after Boo.com’s collapse. VCs began demanding stronger business models, more detailed cash flow projections, and clarity on customer acquisition strategies. Lean startup principles – emphasizing MVPs, feedback loops, and iterative scaling – gained traction as a response to cases like Boo.com.

In essence, Boo.com’s story is a foundational case study in modern startup education. It reminds us that innovation must be grounded in execution, and that a business cannot scale what it has not first stabilized.

11. Comparison with Other Dotcom Failures – Boo.com

Boo.com’s downfall, while spectacular in its own right, closely mirrors many of the themes that defined the dot-com bust. Its collapse is often compared to other high-profile failures like Pets.com, Webvan, and eToys. Each of these companies exhibited a common pattern: over-investment in branding and infrastructure, massive marketing spends, overreliance on first-mover advantage, and an unsustainable burn rate.

Much like Webvan, which invested heavily in infrastructure for online grocery delivery, Boo.com spent vast sums on proprietary technology and international expansion before proving its business model. Webvan’s refrigerated warehouses mirrored Boo.com’s investment in advanced website infrastructure and international offices. Both companies failed because they prioritized growth over financial sustainability.

Pets.com similarly burned through its $300 million funding on national advertising campaigns and inefficient logistics. Like Boo.com, it had high customer acquisition costs and poor unit economics. While Pets.com focused on the U.S. market, Boo.com complicated its operations by launching in 18 countries simultaneously. The geographic overreach compounded its cost base and made coordination nearly impossible.

eToys, another cautionary tale, demonstrated similar weaknesses in supply chain planning and revenue seasonality. Boo.com too underestimated how fragmented logistics, differing market cultures, and currency variations could undercut a unified strategy. While eToys struggled with holiday inventory planning, Boo.com’s multi-currency and multilingual system created UX inconsistencies and tech glitches across platforms.

Kozmo.com, the one-hour delivery startup, also shared Boo.com’s excessive optimism. Kozmo scaled to 11 cities with expensive couriers but couldn’t make a profit on $10 snack deliveries. Boo.com’s bet on luxury and fashion brands online faced a similar challenge: the assumption that consumers would change their buying behavior faster than they actually did.

Despite industry differences, the essence of these failures was the same – misjudging the time it would take for consumer behavior to adapt to the internet, paired with a race to scale before reaching product-market fit. Boo.com didn’t just lose money – it lost the window of opportunity by arriving too soon, spending too much, and leaving no margin for pivoting.

12. Broader Lessons for E-Commerce Startups – Boo.com

Boo.com’s failure has become a classic business school case study for e-commerce mismanagement and premature scaling. Its lessons continue to resonate for startups across industries. One of the foremost takeaways is the danger of prioritizing branding and aesthetics over usability and performance. Boo.com’s site may have been visually stunning, but the underlying tech architecture failed to support a smooth customer experience. At a time when most consumers were using dial-up internet, flashy 3D avatars and heavy page loads created frustration rather than delight.

Second, international expansion should never precede product-market fit. Boo.com’s rush into 18 markets without tailoring for local languages, shopping behaviors, or regulatory standards stretched its operational capacity beyond repair. Modern startups now use lean market entry strategies—testing MVPs in smaller markets, building localized teams, and leveraging partnerships. Boo.com did the opposite: they opened offices globally and hired country managers without first validating demand.

Third, the case underscores the importance of burn control. Boo.com raised over $135 million but spent it in less than two years without a pathway to profitability. This is a warning against vanity metrics. High traffic and brand visibility mean little if conversion rates, repeat usage, and margins are poor. Today’s investors are far more attuned to metrics like LTV/CAC ratios, payback periods, and net revenue retention. Boo.com never had time to assess or optimize these.

The fourth critical lesson is about customer education and trust. Boo.com assumed consumers would be ready to buy luxury fashion online, despite the nascent state of e-commerce trust in 1999. Issues like product fit, returns, and authenticity were significant concerns, especially in high-ticket fashion items. Unlike Zalando or Farfetch, which built trust through liberal return policies and curation, Boo.com never overcame initial resistance.

Finally, Boo.com’s failure highlighted the importance of timing. The company’s vision – to sell premium fashion online – wasn’t wrong. It was simply too early. It took until the late 2000s for the infrastructure, consumer mindset, and logistics to catch up. This echoes the common theme that execution and timing are as vital as vision. Zalando, ASOS, and Net-a-Porter succeeded with similar models years later because they entered at a time when bandwidth, payments, and fulfillment were more mature.

13. Industry Changes Triggered by Boo.com’s Fall – Boo.com

Boo.com’s collapse was a watershed moment in the dot-com timeline. Its high-profile failure sent shockwaves through the venture capital world and became a cautionary tale for future e-commerce investments. One of the most immediate consequences was investor skepticism toward fashion e-commerce. After Boo.com, very few startups could raise funding with a similar vision. Fashion tech was deemed too risky, too early, and too capital-intensive.

This changed only after pioneers like ASOS, Net-a-Porter, and Zalando proved that fashion could work online – provided logistics, UX, and customer confidence were addressed first. Boo.com indirectly helped future companies by showing what not to do. Its fall created space for leaner, more iterative players to enter the market with lower burn and better customer feedback loops.

Moreover, Boo.com’s over-engineered website became a lesson in digital minimalism. The web industry pivoted toward clean, fast, and mobile-friendly design principles. Developers began focusing more on accessibility, load time, and cross-platform functionality rather than flashy design. Google’s later emphasis on Core Web Vitals and page experience metrics had philosophical roots in the lessons taught by early failures like Boo.com.

Logistically, Boo.com’s demise revealed the need for robust, scalable supply chains. Many of its problems stemmed from inadequate supplier integrations, inconsistent warehouse planning, and uncoordinated international operations. As a result, the fashion e-commerce industry began investing in supply chain digitization, 3PL partnerships, and real-time inventory visibility.

Lastly, Boo.com contributed to the cultural shift from blind faith in founders to greater operational scrutiny. Its lavish office spending, private jets, and expensive PR became examples of wasteful startup culture. In the wake of the dot-com bust, VCs began appointing financial controllers and demanding quarterly burn reports. The startup ecosystem matured toward governance, compliance, and operational frugality.

Today, Boo.com is often mentioned alongside Pets.com and Webvan as archetypes of dot-com failure. Yet, unlike them, Boo.com’s concept proved valid over time. It was not a bad idea—it was just poorly timed, excessively funded, and mismanaged. Its story remains essential reading for anyone building in the digital commerce space.

14. Summary – Boo.com

The dot-com bubble was a period marked by boundless ambition, investor euphoria, and an unwavering belief that internet-driven businesses could rewrite the rules of commerce. Among the most iconic cautionary tales from this era was Boo.com, a British fashion e-commerce startup that aimed to become the global hub for online streetwear. Despite raising $135 million in venture capital, Boo.com collapsed within 18 months due to poor site usability, bloated infrastructure, and technology that outpaced consumer bandwidth. Its downfall demonstrated how flashy branding and early mover advantage were no match for operational misalignment and user inaccessibility. Like Boo.com, Webvan pursued an ambitious model – online grocery delivery at scale. It raised nearly $800 million and built state-of-the-art fulfillment centers across the U.S. But Webvan fell into the trap of premature scaling and underestimating the logistical complexity of perishable goods delivery. With a burn rate that exceeded $100 million per quarter, it failed to achieve sustainable demand and declared bankruptcy in 2001.

Kozmo.com, which promised free one-hour delivery of snacks, books, and DVDs, exemplified the dangers of unrealistic unit economics. Despite raising $280 million and generating urban buzz, Kozmo could not make money on $15 orders that cost $25 to fulfill. Expansion across multiple cities worsened its cash flow crisis, and the firm shut down in early 2001. Pets.com, known for its sock puppet mascot, tried to replicate Amazon’s success in the pet supplies market but failed to build a viable logistics model for heavy, low-margin items. With a customer acquisition cost higher than its average order value, and an overdependence on branding, it burned through $300 million before collapsing just nine months after going public. Similarly, Flooz.com attempted to create a universal digital currency before mainstream adoption of e-commerce. It spent aggressively on celebrity endorsements and marketing but failed to build merchant acceptance or consumer trust. A large-scale fraud incident in 2001 ultimately pushed it into bankruptcy, despite its pioneering idea.

GovWorks.com, a civic tech startup featured in the documentary Startup.com, tried to digitize municipal services but was plagued by poor internal management and leadership friction. Although it secured $60 million in funding, the lack of technical focus and political coordination made it impossible to scale across diverse city systems, leading to its closure in 2001. The case of eToys.com is another dramatic rise-and-fall story. It tried to become the Amazon of toys, boasting superior UX, fast delivery, and heavy inventory stockpiling before every holiday season. Yet the business failed to control fixed costs, was too dependent on seasonal revenue, and couldn’t compete with Amazon’s diversified model. At its peak, eToys was worth over $8 billion, but it sold its assets for just over $3 million following bankruptcy.

Pixelon promised a video streaming revolution, claiming it had superior compression technology. After raising over $35 million and staging a star-studded launch party in Las Vegas, its technology failed to perform under scrutiny. Fraud by its founder, who was a convicted felon using a false identity, further damaged its credibility. It collapsed in less than a year. Similarly, iWon.com tried to gamify the internet by giving users cash prizes for using its portal. Backed by Viacom and CBS, it attracted users but failed to retain them or monetize the traffic effectively. With poor ad revenue and no distinct value proposition, it couldn’t sustain operations beyond the crash. eMachines positioned itself as a low-cost PC manufacturer and gained market share through aggressive pricing. But low margins, competition from Dell, and poor after-sales service meant it bled cash and had to be rescued via acquisition.

Netpliance, another dot-com misstep, launched the i-Opener – an internet appliance sold below cost with the hope of profiting from subscription fees. When hackers figured out how to bypass the subscriptions, Netpliance lost its only revenue stream. It faced lawsuits, rebranded, and eventually exited the market. ThinkTools AG, a Swiss firm, claimed to offer AI-driven business decision tools. Its share price soared after an IPO but collapsed when it was revealed the tech was essentially vaporware with no verifiable use cases. Investors lost millions as the company was delisted. Loudcloud, founded by Marc Andreessen, aimed to sell infrastructure-as-a-service before the cloud ecosystem matured. Although visionary, it was too early. The company burned through massive amounts of capital and was eventually sold and restructured into Opsware, which was later acquired by HP.

All these companies shared common patterns: an overreliance on hype, premature scaling, fragile business models, and a detachment from profitability. While many had compelling ideas that later re-emerged in successful forms – like Instacart for Kozmo, AWS for Loudcloud, and Venmo for Flooz – their initial failures offer timeless lessons in execution discipline, capital efficiency, and understanding consumer behavior. Together, they reflect a period where vision often ran faster than reality, where capital replaced strategy, and where the market, in its frenzy, forgot the fundamentals of business.