Abstract – Pets.com

This case study examines the rise and fall of Pets.com, one of the most emblematic failures of the dotcom bubble era. Founded in 1998, Pets.com attempted to disrupt the pet supply retail market through an online-only model. Despite strong backing from Amazon and other venture capital firms, Pets.com collapsed less than one year after its initial public offering. This analysis explores the company’s strategic missteps, flawed unit economics, unsustainable customer acquisition costs, and broader implications for e-commerce ventures operating in capital-fueled speculative markets.

1. Company Background – Pets.com

- Company Name: Pets.com Inc.

- Founded: August 1998

- Headquarters: San Francisco, California

- Founders: Greg McLemore (initial concept), Julie Wainwright (CEO and primary face post-VC funding)

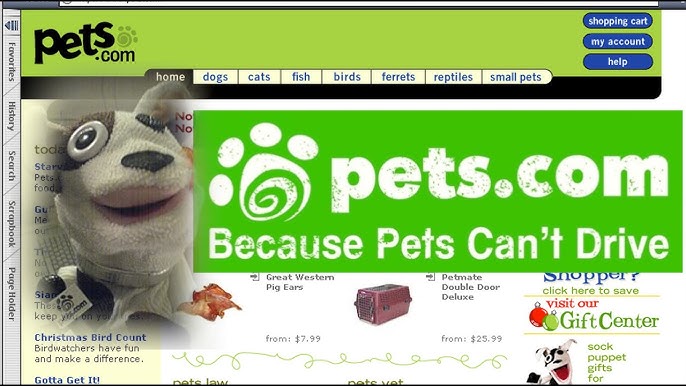

- Mascot: Sock puppet dog (used prominently in national marketing campaigns)

- Tagline: “Because pets can’t drive.”

- Business Model: Online retailer of pet supplies and food delivered directly to consumers.

- IPO Ticker: IPET (Nasdaq)

2. Founding and Investor Landscape – Pets.com

Key Investors of Pets.com:

- Amazon.com: Held ~30% stake by 1999

- Hummer Winblad Venture Partners

- Bowland Venture Partners

- Idealab!

- Sylvester Stallone (angel investor, minor stake)

Amazon’s investment included logistical support and strategic advisement, including integration with its distribution network.

3. Timeline of Key Events of Pets.com

| Date | Event |

| August 1998 | Pets.com founded |

| February 1999 | First major VC funding round closes |

| November 1999 | Amazon invests $50 million in exchange for ~30% ownership |

| February 2000 | Company airs $1.2M Super Bowl ad featuring sock puppet |

| February 2000 | IPO on Nasdaq at $11/share |

| November 2000 | Company ceases operations and begins liquidation |

| January 2001 | Assets auctioned off; domain sold for $1.2 million to PetSmart |

4. Venture Funding – The Pets.com

Venture Funding – Pets.com

- Total VC Raised: $110 million+

- Amazon Contribution: $50 million

- Other VC Contributions: $60+ million from Hummer Winblad, Bowman Capital, and others

IPO Metrics – Pets.com’s Pop & Drop

- Date: February 2000

- IPO Price: $11/share

- Shares Issued: 7.5 million

- Capital Raised in IPO: $82.5 million

- Initial Market Cap: ~$300 million

- Closing Share Price (Nov 2000): $0.19

- Post-IPO Lifespan: 268 days

Revenue and Losses

| Metric | 1999 | Q1–Q3 2000 |

| Revenue | $619,000 | $5.8 million |

| Net Loss | $61.8 million | $66 million |

| Gross Margin | Often negative | Still negative |

| Burn Rate (1999–2000) | $1-2 million/month | Peaked at $10 million/month during ad campaigns |

Key Metrics – What Pets.com Paid

- Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC): >$100

- Average Order Value (AOV): ~$40

- Shipping Subsidy Per Order: $10–$20

- Advertising Spend (1999): $35 million

- Super Bowl Ad Cost (2000): $1.2 million

- Number of Employees at Peak: ~320

5. Market Context – Pets.com in a $23B Bet

The late 1990s saw an unprecedented influx of capital into web-based businesses with little or no revenue. The dominant thesis of the period was “first-mover advantage” – the belief that market share and brand awareness justified outsized investments ahead of profitability. The U.S. pet industry was valued at $23 billion in 1999, making it a ripe vertical for disruption. Investors believed Pets.com would replicate the success of Amazon in books or eToys in toys.

6. Strategic Failures – Pets.com

6.1 Unit Economics – Pets.com’s Heavy Losses

The core flaw in Pets.com’s model was shipping high-weight, low-margin items – such as 50-pound bags of dog food – directly to consumers at a loss. Fulfillment and warehousing costs were inordinately high, and the company offered free or heavily subsidized shipping to encourage customer acquisition.

- Gross margins remained negative across most SKUs

- Logistic costs were not scalable with AOVs below $50

6.2 Consumer Behavior Misalignment – Pets.com

Unlike music or books, pet food and supplies were often impulse or last-minute purchases, for which physical retail offered faster gratification. Additionally:

- Brand loyalty in the pet market was high

- Pet owners often preferred in-store purchasing for perishables and custom-fit items

6.3 Overspending on Marketing – Pets.com

Despite minimal revenue, the company spent more than 5x its 1999 revenue on marketing alone, including:

- Television and print ads

- National campaigns featuring the sock puppet mascot

- Super Bowl ad spend that delivered brand recognition, but not customer loyalty

6.4 Poor Timing of IPO – Pets.com

The Pets.com IPO in February 2000 occurred weeks before the NASDAQ Composite Index peaked on March 10, 2000.

When investor sentiment collapsed in Q2, Pets.com’s losses and unsustainable model became unacceptable to public markets.

7. The Collapse – Pets.com Shuts Down

On November 7, 2000, Pets.com’s board voted to cease operations. Reasons cited included:

- Inability to secure additional capital

- No clear path to profitability

- Structural unviability of the business model

Key outcomes:

- 320+ employees laid off

- Domain “Pets.com” sold to PetSmart for $1.2 million

- Mascot rights sold to BarNone.com

- Amazon wrote off its investment in Q4 2000

- Public shareholders saw 98% value erosion in < 9 months

8. Strategic Implications and Industry Lessons – What Pets.com Taught Us

| Strategic Theme | Implication |

| Logistics Matters | E-commerce must align unit economics with shipping and order value |

| Awareness ≠ Retention | Brand recognition (e.g., sock puppet) did not translate into user loyalty |

| Capital is Not Immunity | Even with Amazon’s backing, Pets.com failed due to unsustainable economics |

| Product-Market Fit | Misreading consumer behavior can doom even well-funded ventures |

| Premature IPO | Companies without revenue models should not go public under pressure |

9. Evolution – Pets.com vs. Today

While Pets.com failed, the online pet supply sector did not. The eventual success of:

- Chewy.com (founded 2011, sold to PetSmart for $3.35 billion in 2017)

- BarkBox (subscription-based, focused on personalization)

…demonstrates that timing, fulfillment infrastructure, and customer experience design were the real missing links – not market demand.

10. PESTEL Analysis – Pets.com In Its Time

| Category | Factor | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Political | E-commerce Deregulation | In the 1990s, online commerce operated in a lightly regulated environment. |

| Pro-Startup Environment | California policies were favorable to startups and venture capital-driven tech firms. | |

| No Online Sales Tax | Most U.S. states had not implemented taxes on internet purchases, making online goods more competitive in price. | |

| Economic | Dot-com Boom | Late 1990s saw strong GDP growth, with Silicon Valley attracting billions in VC funding. |

| Overcapitalization | An abundance of VC money flooded the tech sector; Pets.com raised $82.5M including Amazon’s investment. | |

| Market Collapse | Nasdaq rose 400% from 1995 – 2000, but collapsed in March 2000, drying up funding and investor interest almost overnight. | |

| Social | Pet Ownership Growth | 61% of U.S. households owned pets, and pet spending was increasing consistently. |

| Pet Humanization | Pets were increasingly treated as family members, boosting demand for quality products. | |

| Online Buying Skepticism | While people began to buy online, trust and adoption for essentials like pet food was still low. | |

| Technological | Limited Internet Infrastructure | Most users were on dial-up; broadband was not yet widespread, affecting shopping speed and convenience. |

| Primitive Logistics Tech | No modern integrations (e.g., FedEx/UPS APIs were basic); real-time tracking or optimization was unavailable. | |

| No Mobile Commerce | Smartphones didn’t exist, so there was no app-based engagement or mobile ordering ecosystem. | |

| Environmental | ESG Irrelevant | Environmental concerns like carbon footprint were not on investor or consumer radar at the time. |

| Heavy Shipping Model | Pets.com’s model was logistics-heavy, resulting in a high footprint – but this wasn’t scrutinized in the late ’90s. | |

| Legal | Lax IPO Oversight | SEC regulations were lenient pre-Sarbanes–Oxley Act (2002), allowing early IPOs with minimal operational proof. |

| Weak Consumer Protections | Few laws protected customers from failed deliveries or e-commerce scams, contributing to trust issues. |

11. SWOT Analysis – Pets.com’s Strategic Profile

| Type | Factor | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | First-Mover | Entered the pet e-commerce space early, capturing media and investor attention. |

| Amazon-Backed | Gained logistics support, credibility, and funding from Amazon. | |

| Strong Branding | National campaigns and Super Bowl ads built mass awareness (e.g., Sock Puppet mascot). | |

| Market Interest | Growing consumer affection and spending on pets created a promising market backdrop. | |

| Weaknesses | Unit Economics | Negative gross margins, high CAC, and poor LTV made the model unsustainable. |

| Logistics Issues | Relied on third-party logistics, resulting in fulfillment delays and no cost efficiency. | |

| Low Retention | No auto-ship, loyalty, or personalization features to encourage repeat orders. | |

| Product Fit | Tried to sell heavy, low-margin products like pet food online – logistically inefficient and poorly aligned with user expectations. | |

| Opportunities | Market Size | $23B+ pet economy in the U.S. was under-digitized and primed for disruption. |

| E-commerce Boom | The broader shift toward online shopping created growth headroom. | |

| Subscription Model | Recurring orders (e.g., food, litter) were ideal for subscription – untapped by Pets.com. | |

| Adjacent Verticals | Huge cross-sell potential in pet insurance, grooming, vet care, etc. – never explored. | |

| Threats | Rising Competition | Petopia.com, Amazon’s own marketplace, and local retailers threatened both price and convenience advantage. |

| Capital Tightening | Post-bubble crash dried up investor funding and IPO access. | |

| Consumer Behavior | High price sensitivity and lack of trust in online delivery of essentials led to churn. |

12. Porter’s Five Forces Analysis – Pets.com

| Force | Analysis | Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Threat of New Entrants | High | The pet e-commerce space saw a surge in new entrants after Amazon’s investment validated the market. Pets.com lost its first-mover advantage quickly. |

| 2. Bargaining Power of Suppliers | Medium | The supply base was dominated by a few players like Nestlé Purina and Mars Petcare. Pets.com had no exclusive deals and was selling commoditized goods. |

| 3. Bargaining Power of Buyers | High | Customers could switch instantly at no cost. Price sensitivity was high, and Pets.com lacked loyalty programs or differentiated offerings. |

| 4. Threat of Substitutes | High | Physical pet stores and supermarkets offered instant purchase options. Other online stores without subscription models also undercut Pets.com. |

| 5. Industry Rivalry | Very High | Competing firms like WebVan, Petopia.com, and Amazon led to fierce price wars. Excessive ad spend and shrinking margins defined the market. |

13. Strategic Missteps – Inside Pets.com

13.1 Misaligned Cost Structure – Pets.com

- Shipping 50 lb dog food with free delivery led to losses of $3-$4 per order

- Gross margins were often below zero

13.2 Overemphasis on Marketing – Pets.com

- $35M ad spend in 1999 vs. $619K revenue

- Super Bowl ad ($1.2M) drove traffic, but no retention

13.3 Poor Financial Planning – Pets.com

- IPO raised $82.5M but was quickly consumed by:

- Warehousing

- Ad spend

- Payroll

- Warehousing

- Company never approached breakeven unit economics

13.4 Weak Technology Stack – Pets.com

- No dynamic pricing

- No predictive reordering

- No warehouse automation like Amazon was beginning to experiment with

14. Impact Metrics – Pets.com’s Crash

| Metric | Value |

| IPO Valuation | ~$300 million |

| Revenue in 1999 | $619,000 |

| Total Losses by Q3 2000 | $66 million |

| Ad Spend (1999–2000) | ~$50 million |

| Net Loss Per Order | $3–$4 |

| CAC vs. AOV | $100+ vs. ~$40 |

| Burn Rate | ~$10 million/month by late 2000 |

| Final Share Price | $0.19 |

| Value Lost (Market Cap) | ~$297 million wiped out within 268 days |

15. Broader Insights – Pets.com Case

| Lesson | Explanation |

| Don’t prioritize brand over viability | Pets.com had visibility but not viability. The sock puppet couldn’t fix logistics. |

| Funding ≠ Fundamentals | Amazon’s $50M did not prevent collapse because unit economics were broken |

| Fulfillment = Core, not Add-on | E-commerce success depends heavily on optimizing shipping, warehousing, returns |

| Focus on LTV:CAC ratio | Pets.com spent over $100 to acquire a customer worth less than $40 |

| Timing is everything | E-commerce needed better internet penetration, logistics tech, and consumer trust – all of which Chewy leveraged a decade later |

16. Comparative Note: Chewy vs. Pets.com

| Factor | Pets.com (2000) | Chewy.com (2011–2017) |

| Year Founded | 1998 | 2011 |

| Funding Raised | $110M | $350M |

| Avg. Order Value | ~$40 | $75–85 |

| CAC | >$100 | ~$40–50 |

| Fulfillment | Outsourced | Built in-house network of warehouses |

| Loyalty Tools | None | Autoship, CRM, vet follow-up |

| Business Model | Price-led | Experience-led |

| Exit | Shutdown in <3 years | Acquired by PetSmart for $3.35B |

16. Leadership and Governance Flaws – Pets.com

16.1 Leadership Gap – Pets.com

- CEO Julie Wainwright had prior experience at Reel.com, another dotcom failure.

- Board lacked deep operational experience in logistics or supply chain, which was core to success in pet retail.

- Strategic decisions (e.g., Super Bowl ad spend, premature IPO) reflected a marketing-first mindset rather than an operations-led strategy.

16.2 Weak Corporate Governance – Pets.com

- No sustainability metrics reported in quarterly filings.

- Overly focused on revenue growth and user acquisition without profitability benchmarks.

- Failure to challenge unit economics during board and investor discussions.

17. The Sock Puppet Problem – Pets.com

- The sock puppet became a pop culture icon – appearing on Good Morning America, People Magazine, and Late Night with Conan O’Brien – but overshadowed the product itself.

- Consumers remembered the ad and mascot, but not why they should use the platform.

- Conversion rate from advertising was extremely poor:

Less than 1.5% of site visitors completed a purchase (per SEC risk disclosure).

18. Bubble Burst – Pets.com’s Final Blow

- Pets.com’s collapse was directly accelerated by the bursting of the Nasdaq bubble in March 2000.

- Venture capital inflows shrank 81% in 2001 compared to 2000 (source: NVCA data), cutting off potential future funding.

- The company had initiated efforts to raise additional capital in mid-2000 – but investor appetite vanished due to broader dotcom failures.

19. Product Complexity & Inventory Issues – Pets.com

- Pets.com attempted to stock a wide SKU catalog (over 15,000 items) early on.

- But their demand forecasting tools were weak – leading to:

- Overstocking of low-demand items

- Stockouts for high-volume staples

- High inventory carrying costs

- Higher return rates due to incorrect sizing and perishables

- Overstocking of low-demand items

20. Lack of Strategic Partnerships with Vets or Groomers – Pets.com

- Unlike Chewy (which partnered with vet clinics and offered autoship for prescription diets), Pets.com never built strategic B2B pipelines.

- Missed opportunity to build recurring revenue through:

- Subscription-based refills

- Vet referrals

- Loyalty bundles (food + grooming + insurance)

- Subscription-based refills

21. Behavioral Economics Oversight – Pets.com

- Pet owners often view pet care as emotionally driven purchases – they prefer personal advice and hands-on interaction.

- Pets.com failed to capitalize on emotional triggers (pet stories, personalization, health tracking), which Chewy later mastered via:

- Handwritten notes

- Birthday cards for pets

- 24/7 customer service with empathetic tone

- Handwritten notes

22. Post-Mortem Industry Ripple Effects

- Investors became cautious of logistics-heavy e-commerce for nearly a decade.

- “Pets.com syndrome” became a term in Silicon Valley to refer to:

“High burn, low margin, high-visibility startups with no path to breakeven.” - Venture capital began asking for:

- Clear CAC:LTV ratios

- Working gross margins

- Unit-level contribution models

- Clear CAC:LTV ratios

Summary

When Pets.com collapsed in late 2000, it wasn’t just the death of another overfunded internet startup – it was a watershed moment for Silicon Valley and the venture capital ecosystem at large. The failure of this once-hyped company sent shockwaves through the tech and investment community, triggering a deep reassessment of how startups were evaluated, funded, and scaled in the digital age.

From Poster Child to Cautionary Tale

In just 268 days after going public, Pets.com lost nearly 98% of its market value, burning through over $110 million in VC funding – including a $50 million stake from Amazon. The company’s downfall was so dramatic and public that “Pets.com Syndrome” became a common industry term used to describe any startup with:

- High visibility,

- Unsustainable unit economics,

- No clear path to profitability, and

- A tendency to prioritize brand awareness over operational strength.

What made the fall of Pets.com particularly sobering was the stark contrast between perception and performance. At its peak, it was featured in the Super Bowl, had a nationally beloved sock puppet mascot, and enjoyed the backing of a tech titan (Amazon). Yet, it couldn’t survive a market downturn because it had no viable business engine underneath the surface.

Redefining the Rules for Startups

Before Pets.com, the venture capital community was primarily obsessed with eyeballs, traffic, and brand recall. Startups were being funded not for their business fundamentals but for their potential to become the next “Amazon for X.”

After the Pets.com crash, VCs and public markets completely changed their expectations, shifting away from speculative spending and toward financial discipline and unit economics. This shift led to five key ripple effects:

1. Increased Emphasis on Unit Economics

Investors began to scrutinize CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost), LTV (Lifetime Value), Gross Margins, and Contribution Margins like never before. Pets.com had a CAC of over $100 while selling products with an AOV of $40, subsidizing shipping by another $10–$20 per order. This kind of imbalance became a red flag in the years that followed.

2. Logistics and Fulfillment Moved Front and Center

Pets.com outsourced most of its logistics and had no in-house control over fulfillment, warehousing, or delivery optimization. After its collapse, e-commerce startups realized that fulfillment is not a backend task – it’s a core differentiator. Companies like Chewy later succeeded precisely because they built robust fulfillment operations from the ground up.

3. Brand ≠ Viability

Pets.com spent more than $35 million on advertising in a single year, including $1.2 million on a Super Bowl ad, trying to manufacture trust and recognition. But when consumer behavior didn’t translate into purchases, it exposed a critical lesson: awareness without conversion is meaningless. Future startups were forced to prioritize retention, product-market fit, and repeat behavior over vanity metrics.

4. IPO Readiness Became Stricter

Pets.com went public far too early, just months before the dot-com bubble burst. At the time of its IPO, it had minimal revenue, negative margins, and no clear profitability roadmap. Post-collapse, regulators and investors became wary of premature IPOs, ultimately leading to stricter oversight (e.g., Sarbanes–Oxley Act in 2002) and more rigorous expectations for IPO candidates.

5. Long-Term Caution Around Low-Margin, High-Volume Businesses

The idea of selling heavy, low-margin items like dog food online – and losing money on every transaction – became a textbook example of what not to do. Investors became cautious of any business where volume growth didn’t improve margins. For almost a decade after, logistics-heavy consumer internet companies faced significant skepticism.

A Blueprint for the Future: Learning from Failure

Despite its failure, Pets.com left behind a valuable blueprint. The next generation of pet e-commerce startups, especially Chewy.com, BarkBox, and PetFlow, closely studied the Pets.com debacle. They focused on:

- Subscription models like Autoship

- CRM integrations with vet services

- Operational excellence in warehousing and logistics

- Customer experience personalization

- Sustainable CAC:LTV ratios

Chewy’s rise and eventual $3.35 billion acquisition by PetSmart in 2017 proves that the market opportunity Pets.com identified was real – the execution was the only thing that failed.

Legacy of Pets.com in Modern VC Culture

Today, many investors reference Pets.com in pitch meetings to assess:

- Whether a founder truly understands their unit economics

- Whether a business model can scale profitably

- Whether a brand is distracting from operational flaws

The name “Pets.com” is now industry shorthand – a single phrase that evokes an entire playbook of strategic errors: overfunding, premature IPO, poor logistics, bad customer retention, and marketing overreach.

Final Insight: Pets.com Didn’t Fail Because of the Idea – It Failed Because of Execution

The crash of Pets.com permanently shifted the trajectory of internet business development. It showed that timing, infrastructure, and execution matter far more than hype, media visibility, or investor endorsement. It forced both entrepreneurs and investors to confront uncomfortable truths about scalability and sustainability in the internet age.

In that sense, Pets.com didn’t just crash – it educated an entire generation of founders.